မြန်မာပစ္စည်း ၄၀၀၀ ကျော်ရှိတဲ့ ဗြိတိန် ပြတိုက် Britiish Museum https://youtu.be/C45Dl86gmcY?si=wHL-r69WHu_8T6hx

La Gioconda del Prado is an extraordinary early copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Spain.

Long thought to be a later, inferior replica, the painting underwent extensive restoration and analysis in the early 2010s, revealing its remarkable significance.

Scientific studies, including infrared imaging, showed that the painting was created simultaneously with the original Mona Lisa, likely in Leonardo’s own workshop.

The copy mirrors many underdrawings and changes found in Leonardo’s version, suggesting it was painted alongside the master’s work, possibly by a close pupil.

Art historians now believe that the artist behind the Prado copy was likely Francesco Melzi or Salaì, two of Leonardo’s most trusted apprentices.

The background, once obscured by black overpaint, was revealed to match the original Tuscan landscape seen in Leonardo’s version.

Unlike the original, which has darkened and cracked over centuries, the Prado version retains brighter colors and sharper details, offering insight into how the Mona Lisa might have originally looked.

The painting provides invaluable context for understanding Leonardo’s techniques, workshop practices, and the evolution of Renaissance portraiture.

Its rediscovery elevated it from a forgotten copy to one of the most important comparative works related to the Mona Lisa.

Today, La Gioconda del Prado stands as a rare and vital companion to Leonardo’s masterpiece, helping scholars and viewers alike glimpse the creative world of the High Renaissance.

1- Archeology ,art and history of ancient world by Haley Nguyen

In the heart of Rome, on the Quirinal Hill, a remarkable discovery was made in March 1885 during excavations near the ancient Baths of Constantine. Unearthed from the earth was a breathtaking bronze statue of a seated man—worn, weary, his head bowed, his body marked by the brutal toll of combat. This wasn’t just any statue; it was a lifelike remnant of ancient history, later known as The Boxer at Rest, a masterpiece that stunned the world of art and archaeology.

Believed to date from the 3rd century BCE during the late Hellenistic period, the statue depicts a boxer in a rare moment of vulnerability and exhaustion. He sits hunched on a rock, his muscular frame slumped, his expression heartbreakingly human: a broken nose, swollen lips, sunken eyes, open wounds, and deep scars—all rendered with astonishing realism. Red copper inlays were used to simulate fresh blood and raw injuries, a testament to the artist’s extraordinary technique and attention to detail.

What sets this work apart is not only its technical brilliance, but the sheer emotional power it conveys. Unlike classical sculptures that idealized victory and strength, Hellenistic art dared to portray suffering, fatigue, and humanity. This boxer isn’t celebrating triumph—he’s simply enduring. Possibly the work of a Greek master later brought to Rome during a period of cultural admiration for Greek art, the statue’s creator remains unknown, adding to its mystery. Today, The Boxer at Rest resides in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, not merely as a relic of the past, but as a timeless reminder of the fragility of the human spirit and the profound truth that even heroes can break.

2 – Archeology &Ancient Civilizations

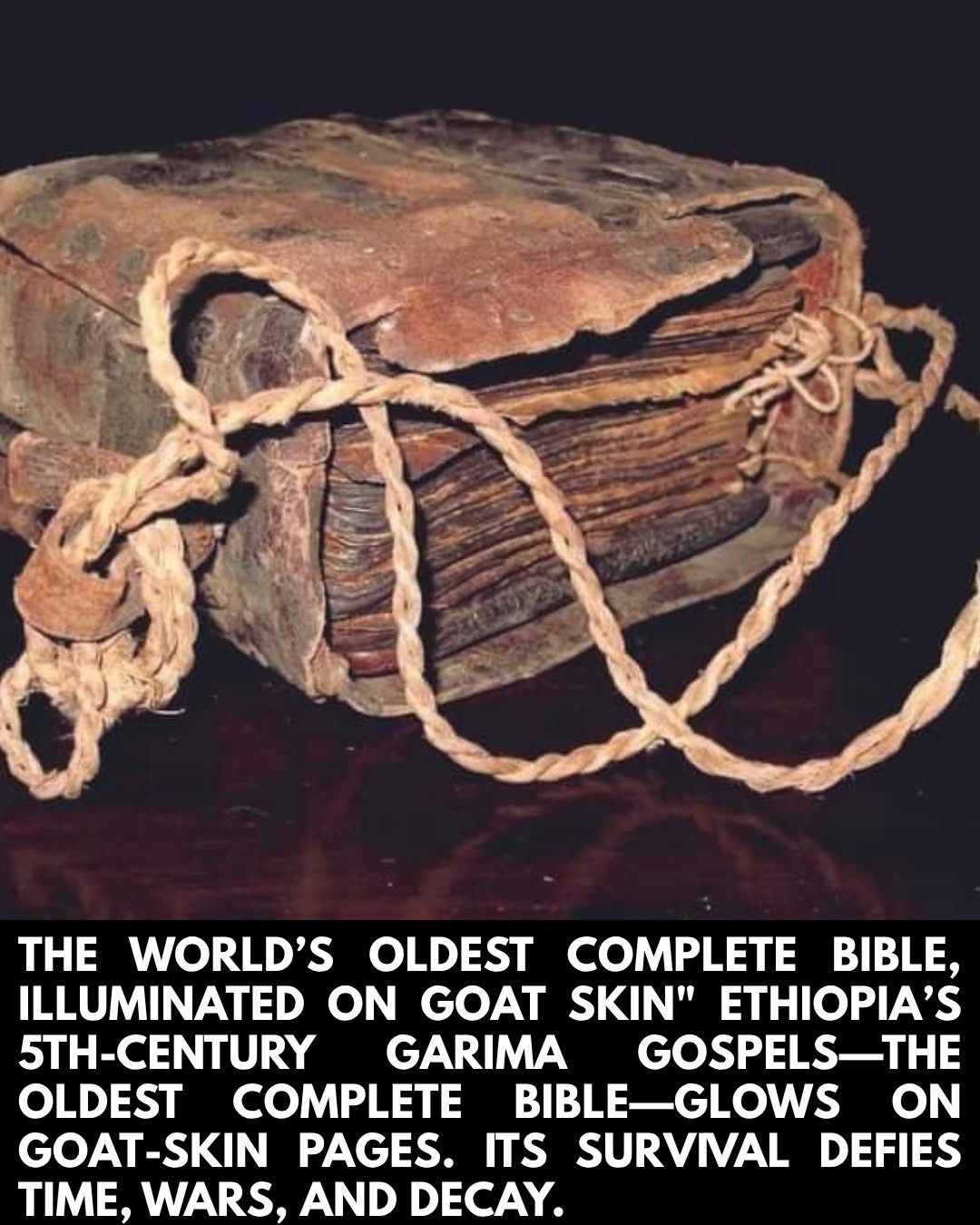

The oldest and most complete Bible in the world is the Codex Sinaiticus, dating back to the 4th century CE.

It was discovered in the mid-19th century at St. Catherine’s Monastery at the base of Mount Sinai, Egypt.

Written in Greek on parchment, the Codex contains the entire New Testament and much of the Old Testament, offering a rare glimpse into early Christian scripture.

Its text differs in several places from later standardized Bibles, shedding light on how biblical texts evolved over centuries.

Today, parts of the Codex are preserved in institutions across the UK, Germany, Russia, and Egypt, and it remains a cornerstone of biblical scholarship.

See more: https://www.ganjingworld.com/vi-VN/video/1h8i2si6gcv3Bvu1sQJDdTHTT1i31c

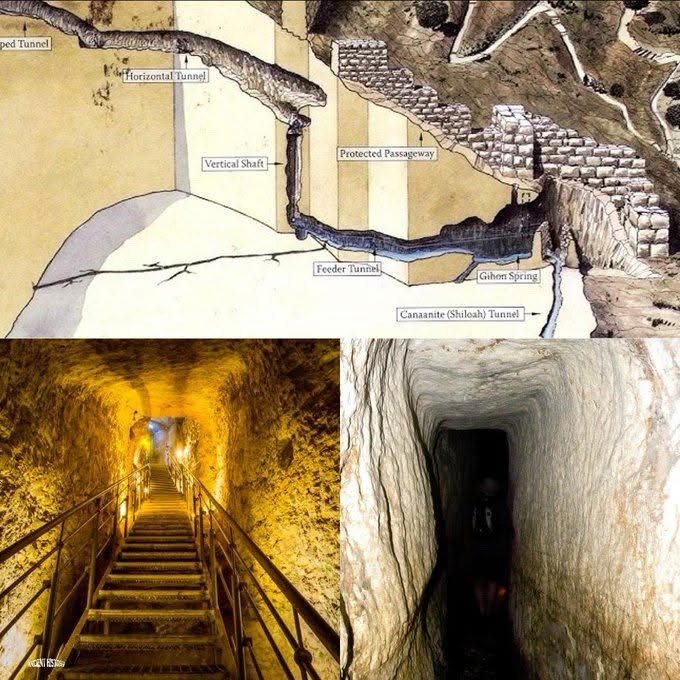

3- Deep beneath the ancient city of Jerusalem, hidden in the bedrock of history, lies Hezekiah’s Tunnel—also called the Siloam Tunnel. Carved between 701-681 BC, during the reign of King Hezekiah, this remarkable passage was designed to divert water from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam, securing life amid the looming threat of an Assyrian siege.

This 533m long tunnel was painstakingly hewn from solid limestone using nothing but hand tools—no light, no machines. Even more astonishing, two teams started digging from opposite ends and met, almost perfectly, in the middle. A silent testament to human precision, resilience, and ingenuity, still echoing through its narrow, water-worn walls. Walking its winding corridor is like stepping into the pulse of an ancient mind—a place where fear, faith, and engineering converged. The chisel marks whisper stories, the damp stone breathes survival, and every bend in the darkness becomes a thread connecting past to present.

4- An astonishing archaeological discovery was made near Weymouth, UK, where the skeletal remains of 51 young Viking warriors were unearthed in a mass grave.

The site, found during road construction in 2009, revealed that the men had been brutally executed, many showing signs of beheading and dismemberment.

Radiocarbon dating placed the remains in the early 11th century, a time of violent clashes between Anglo-Saxons and Norse invaders.

The warriors, mostly aged between 16 and 25, appeared to have been stripped of their weapons and armor before their execution.

Isotopic analysis of their teeth indicated that the men came from Scandinavia, most likely Norway or Sweden, confirming their Viking origin.

The burial was unusual—skulls separated from bodies, stacked in a pit—suggesting a display of dominance, possibly as a warning to other invaders.

This execution may have occurred during the reign of King Æthelred the Unready, who ordered mass killings of Danes in 1002 in what became known as the St. Brice’s Day massacre.

The discovery provides crucial insight into the brutality of early medieval warfare and the resistance faced by Viking raiders in England.

It also challenges romanticized views of the Viking Age, revealing the harsh and often short lives of young warriors.

Today, the Weymouth warriors stand as a grim but powerful reminder of the brutal struggles that helped shape early English history.

5- The Sarcophagi of San Pietro in Bevagna – A Roman Era Maritime Mystery

Off the coast of San Pietro in Bevagna, Italy, lies a captivating underwater archaeological site: a 3rd-century Roman shipwreck discovered just 70 meters from shore.

This remarkable find, explored by the Orca Diving Center, contains a cargo of 20 unfinished white marble sarcophagi, offering a glimpse into ancient maritime trade and craftsmanship.

These intricately carved sarcophagi, likely intended for elite burials, were never completed or used, raising questions about their purpose and the ship’s ill-fated journey.

Were they destined for a prominent Roman city? Why were they abandoned beneath the waves?

The site, accessible through guided dives with Orca Diving Center, showcases the challenges of underwater archaeology, requiring specialized techniques to preserve and study the relics. The sarcophagi, partially buried in sediment, reflect the dynamic nature of marine environments, where currents and time threaten preservation.

This discovery, linked to the broader context of Roman trade routes, possibly connecting to regions like Egypt, underscores the significance of Salento’s coastal waters in antiquity.

The mystery of the sarcophagi continues to intrigue archaeologists and divers alike, inviting exploration into a silent chapter of history.

6-

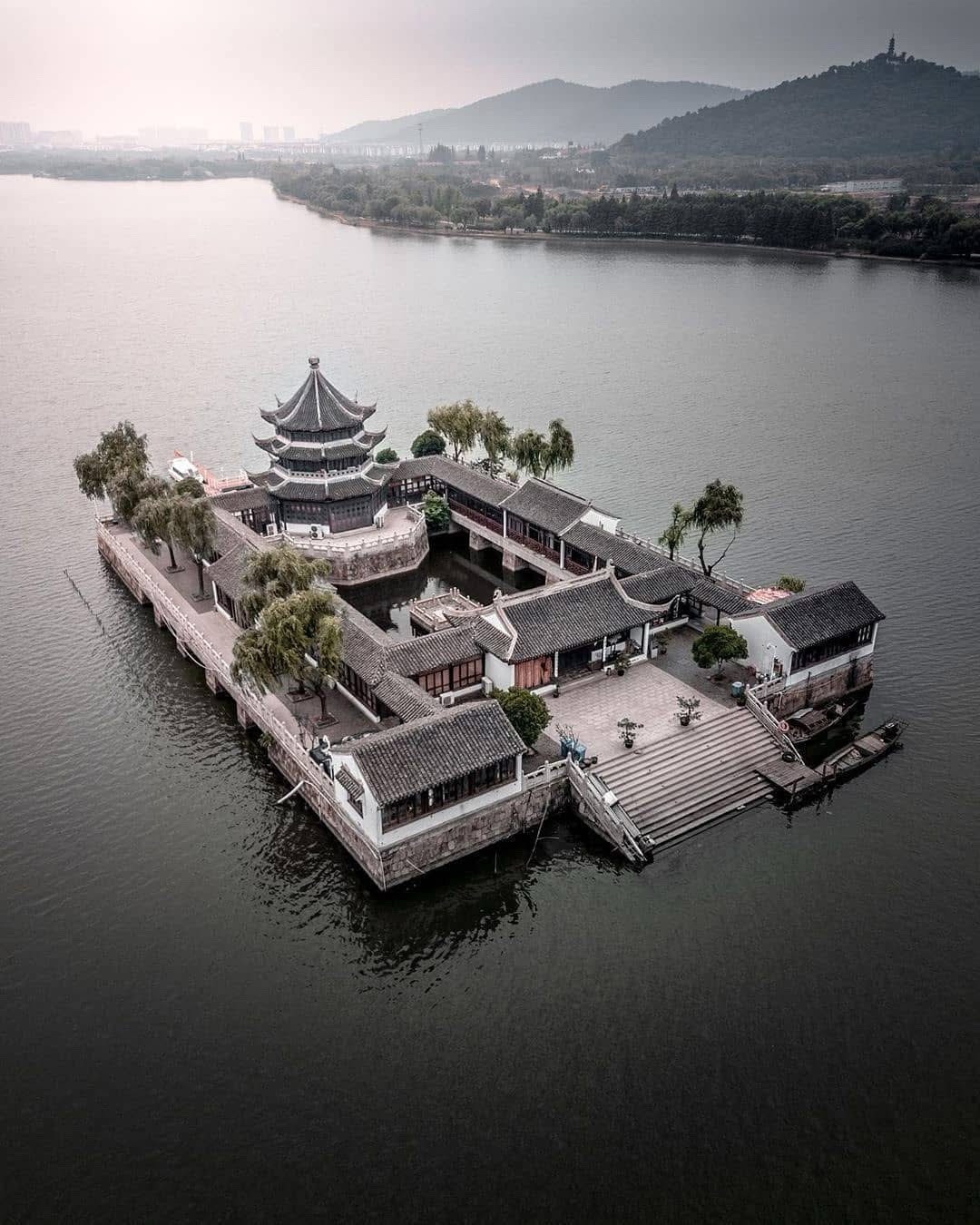

The Tianjing Pavilion was constructed in 1612 during the Ming dynasty, gracefully situated on a small island at the center of Lake Shi in Suzhou, China.

Commissioned by local scholar-officials, the pavilion was designed as a serene retreat for poetry, painting, and scholarly gatherings in harmony with nature.

Its name, “Tianjing,” meaning “Mirror of Heaven,” reflects the tranquil waters surrounding it, which perfectly mirror the sky and the pavilion itself.

Built in the classical Jiangnan garden style, the pavilion features elegant wooden architecture, curved roofs, and intricate latticework that complements the surrounding landscape.

Suzhou, known as the “Venice of the East,” was a cultural hub during the Ming dynasty, and Tianjing Pavilion epitomized the refined aesthetic values of the literati class.

The location on Lake Shi symbolized spiritual detachment and a connection to Daoist ideals of balance between humans and the natural world.

Over the centuries, the pavilion weathered political changes and natural wear, yet it remained a cherished landmark of Suzhou’s artistic heritage.

It underwent several restorations, particularly during the Qing dynasty and in modern times, preserving its original Ming-era design.

Today, Tianjing Pavilion is part of a larger historical and scenic area, attracting scholars, tourists, and artists who continue the traditions once practiced there.

As a jewel of classical Chinese garden architecture, it embodies the harmony, elegance, and contemplative spirit that defined the cultural landscape of Ming-era Suzhou.

7-

One of the earliest known photographs of a Native American with a wolf, taken in the late 1800s, stands as a timeless testament to the deep spiritual bond between humans and nature.

Far more than a portrait, the image captures a relationship rooted in mutual respect, where the wolf was not feared, but honored as a sacred companion.

In many Indigenous traditions, the wolf symbolized family, loyalty, and endurance—qualities reflected in the lives of those who lived closely with the land.

This historic photograph reveals the reverence Native American cultures held for animals, seeing them not as beasts of burden, but as equals in the cycle of life.

The presence of the wolf in the image underscores its role as a totemic figure, guiding tribes through spiritual journeys and communal values.

For generations, Native peoples observed and emulated the wolf’s hunting strategies, pack hierarchy, and keen survival instincts.

This visual record disrupts the colonial narrative of dominance over the wild, offering instead a glimpse into a worldview of coexistence.

The photograph immortalizes a cultural moment where interspecies respect transcended fear, embodying teachings passed down through oral tradition.

At a time when Indigenous lifeways were under threat, this image quietly affirmed enduring beliefs in the sacredness of all creatures.

Ultimately, the photograph speaks not only of history, but of a worldview—where the howl of the wolf was not a warning, but a welcome.

8-

Around 45,000 years ago, a previously unknown group of early modern humans migrated into Ice Age Europe, entering a continent dominated by harsh climates and Neanderthal populations.

These humans belonged to a now-extinct lineage that left behind only traces in DNA and a few enigmatic archaeological sites.

Genetic studies show that this group interbred with Neanderthals soon after arriving, leaving a legacy of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans.

Their tools, such as sharp blade points and bone ornaments, reveal a blend of African innovation and adaptation to the cold European environment.

Fossils like the Ust’-Ishim man from Siberia and the Bacho Kiro remains in Bulgaria provide rare glimpses into their physical traits and lifestyles.

This branch of humans likely lived in small, mobile groups, following herds of Ice Age megafauna across the tundra and forested plains.

Despite their early arrival, they vanished from the region within a few thousand years, possibly due to climate shifts, competition, or limited population sizes.

Later waves of Homo sapiens from the Near East replaced or absorbed these early pioneers, forming the roots of modern European ancestry.

The brief existence of this lineage represents an important but fragile moment in the peopling of Europe.

Their discovery has reshaped our understanding of human migration, interaction, and extinction during one of Earth’s most challenging eras.

9-

The mummy of Queen Nodjmet dates to approximately 1069–945 BCE, during Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period and the 21st Dynasty.

Nodjmet was a prominent royal woman, believed to be the wife of High Priest Herihor, who assumed kingly titles in Thebes during a time of political fragmentation.

Her mummy was discovered in the Deir el-Bahari Royal Cache (DB320), a hidden tomb where priests reburied royal mummies to protect them from looting.

Alongside her mummy were two funerary papyri, now in the British Museum, which played a crucial role in identifying her and understanding her status.

These texts refer to her as “King’s Mother” and “Mistress of the Two Lands,” underscoring her elevated position in Theban society.

Unlike many queens, her mummification was performed with great care, including the use of fine linen wrappings and a golden mask, indicating her importance.

However, modern research suggests there may have been two women named Nodjmet—one the wife of Herihor, the other his mother—leading to scholarly debate over the mummy’s exact identity.

The embalming practices used in her burial reflect the evolving religious and funerary customs of the 21st Dynasty, including changes in organ removal and resin use.

Her burial, like others from DB320, illustrates the adaptive strategies of priests trying to preserve royal remains amid social and political instability.

Today, the mummy of Queen Nodjmet provides vital insights into royal women’s roles, priestly power, and funerary traditions during a turbulent chapter of ancient Egyptian history.

10-The ancient kauri tree (Agathis australis), native to New Zealand’s North Island, is one of the oldest and largest tree species on Earth, with individual specimens living for over 2,000 years.

These majestic trees date back to the Jurassic period, over 190 million years ago, and are considered living fossils.

Kauri forests once blanketed large parts of northern New Zealand, creating dense ecosystems rich in biodiversity.

Māori people have long revered kauri trees, using their durable timber for waka (canoes) and their resin, known as kauri gum, for lighting and medicinal purposes.

European settlers began extensive logging in the 19th century, drawn to the tree’s immense size and high-quality timber, leading to widespread deforestation.

By the early 20th century, most ancient kauri forests had been decimated, with only a few protected areas remaining, such as Waipoua Forest, home to Tāne Mahuta, the largest living kauri.

Swamp kauri, prehistoric trees preserved in peat bogs for up to 50,000 years, have provided remarkable scientific insights into ancient climates and ecosystems.

Conservation efforts ramped up in the late 20th century, as the ecological and cultural value of the remaining trees became more widely recognized.

In recent decades, kauri dieback disease, caused by a soil-borne pathogen (Phytophthora agathidicida), has posed a grave threat to the remaining trees.

Today, the ancient kauri stands as a symbol of endurance, spiritual significance, and the urgent need for ecological preservation in Aotearoa New Zealand.

11 -The Temple of Bacchus, located in the ancient city of Heliopolis—modern-day Baalbek in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley—is one of the best-preserved Roman temples in the world.

Constructed in the 2nd century CE during the reign of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius, it was dedicated to Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, fertility, and ecstasy.

The temple is renowned for its massive scale and intricate decoration, including finely carved Corinthian columns, richly adorned friezes, and mythological reliefs.

Measuring approximately 66 meters long and 35 meters wide, it rivals the Parthenon in size and showcases the grandeur of Roman imperial architecture in the provinces.

The structure was part of a larger sanctuary complex that included the Temple of Jupiter, making Baalbek one of the most important religious centers in Roman Syria.

Despite centuries of earthquakes, looting, and neglect, the Temple of Bacchus has remained remarkably intact, with its cella walls and 19 of its original 42 columns still standing.

The building reflects a unique fusion of Roman and local architectural traditions, symbolizing the cultural blending that characterized Roman rule in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Rediscovered by European travelers in the 17th and 18th centuries, it soon became a focus of archaeological interest and conservation efforts.

Today, the temple is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a centerpiece of Lebanese heritage, drawing scholars, tourists, and admirers of classical art alike.

The Temple of Bacchus endures as a testament to the engineering prowess and artistic vision of the Roman Empire at its height.

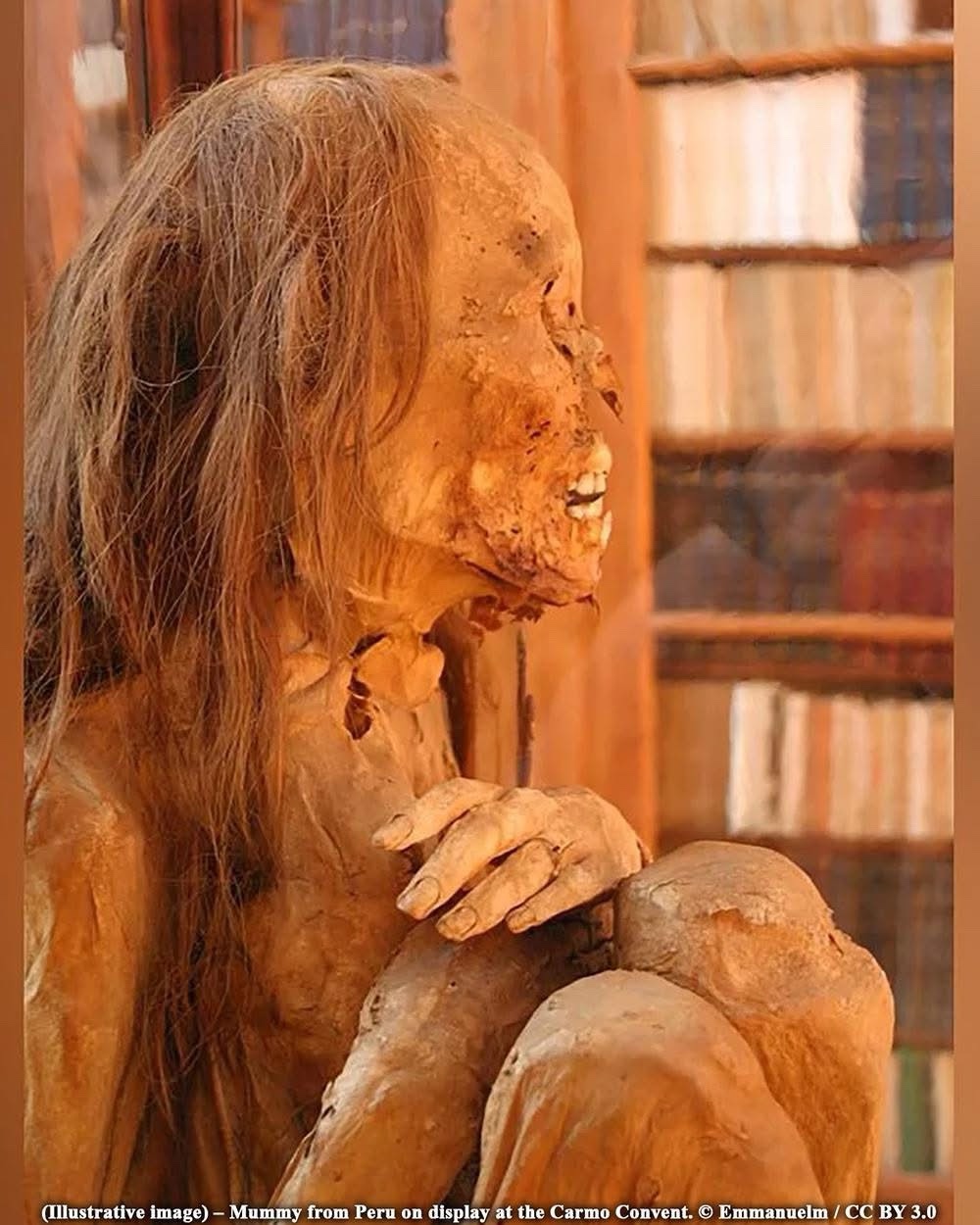

12-In 2022, construction workers installing a gas line in the San Martín de Porres district of Lima, Peru, unexpectedly uncovered a 1,000-year-old pre-Inca mummy.

The mummy was found in a seated, fetal position and wrapped in textiles, a burial style characteristic of ancient Andean funerary practices.

Archaeologists quickly identified the remains as belonging to the Chancay culture, which flourished along Peru’s central coast between 1000 and 1470 CE.

The Chancay were known for their elaborate textiles, pottery, and burial traditions, often interring the dead with offerings such as ceramics and food.

See more: https://www.ganjingworld.com/vi-VN/video/1h3dh42fn2o1gRmA5CvBnP1K917j1c

13-The Library of Celsus, built around 110 CE in the ancient city of Ephesus (modern-day Turkey), was commissioned by Gaius Julius Aquila in honor of his father, Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, a Roman governor of Asia.

Its grand, two-story façade was designed not only as an architectural marvel but also as a mausoleum, with Celsus’s sarcophagus placed in a crypt beneath the library.

The reconstructed façade, carefully restored in the 1970s, features four symbolic female statues representing virtues: Sophia (wisdom), Episteme (knowledge), Ennoia (intellect), and Arete (excellence).

The statue of Arete Kelsou, nestled in one of the central niches, personifies the virtue of excellence, closely associated with Celsus’s public and civic legacy.

Though the original statue was likely removed in antiquity or during looting, the current Arete is a replica based on ancient Roman artistic styles.

The presence of Arete among the library’s symbolic figures reflects the Roman and Greek tradition of honoring moral virtues through personified sculpture.

The Library could hold around 12,000 scrolls and was among the most significant intellectual centers of the Roman world in Asia Minor.

Over the centuries, the structure suffered damage from earthquakes, invasions, and neglect, leaving only remnants until modern archaeological efforts revived its façade.

Today, the statue of Arete Kelsou stands as a symbolic guardian of the ideals the library once embodied—learning, virtue, and civic honor.

The reconstructed Library of Celsus, with Arete gracing its niche, remains one of the most iconic monuments of classical antiquity, drawing visitors from around the world.

14-Old Leanach Cottage is a historic stone dwelling located on the Culloden Battlefield near Inverness, Scotland.

It is widely believed to be the only surviving building from the time of the Battle of Culloden, fought on April 16, 1746.

The battle marked the final confrontation of the Jacobite Rising, where British government forces defeated the Jacobite army led by Charles Edward Stuart.

The cottage likely belonged to a local crofter and may have been used to shelter the wounded during or after the brutal conflict.

Built using traditional materials such as turf, stone, and thatch, the structure reflects typical Highland domestic architecture of the 18th century.

After centuries of exposure and wear, the cottage was restored in the 19th century and again in the 20th to preserve its historical integrity.

The building has served various purposes over time, including as a museum and interpretive center for battlefield visitors.

Its proximity to the heart of the battlefield gives it unique significance as a witness to the violent end of the Jacobite cause.

Managed by the National Trust for Scotland, the cottage remains a poignant symbol of the lives affected by the battle.

Today, Old Leanach Cottage stands as a haunting and evocative reminder of one of the most decisive and tragic episodes in Scottish history.

Old Leanach Cottage is a historic stone dwelling located on the Culloden Battlefield near Inverness, Scotland.

It is widely believed to be the only surviving building from the time of the Battle of Culloden, fought on April 16, 1746.

The battle marked the final confrontation of the Jacobite Rising, where British government forces defeated the Jacobite army led by Charles Edward Stuart.

The cottage likely belonged to a local crofter and may have been used to shelter the wounded during or after the brutal conflict.

Built using traditional materials such as turf, stone, and thatch, the structure reflects typical Highland domestic architecture of the 18th century.

After centuries of exposure and wear, the cottage was restored in the 19th century and again in the 20th to preserve its historical integrity.

The building has served various purposes over time, including as a museum and interpretive center for battlefield visitors.

Its proximity to the heart of the battlefield gives it unique significance as a witness to the violent end of the Jacobite cause.

Managed by the National Trust for Scotland, the cottage remains a poignant symbol of the lives affected by the battle.

Today, Old Leanach Cottage stands as a haunting and evocative reminder of one of the most decisive and tragic episodes in Scottish history.

15-The “Dragon Man” skull, discovered in Harbin, China in 1933 and long kept hidden, was officially named Homo longi in 2021, sparking intense debate about its place in human evolution.

Recent groundbreaking analyses have now confirmed that this ancient hominin is, in fact, a Denisovan — the elusive cousins of Neanderthals and modern humans.

This marks the first time scientists can confidently link a nearly complete skull to the Denisovans, previously known only from fragmentary fossils like teeth and finger bones.

The Dragon Man skull is massive, with a large braincase, thick brow ridges, and a surprisingly flat face, offering the first detailed look at Denisovan anatomy.

Genetic studies of Denisovan DNA from Siberian caves had hinted at their widespread presence in Asia, but their appearance remained a mystery — until now.

The revelation ties together decades of puzzling fossil finds across East Asia and supports theories that Denisovans were a diverse and adaptable population.

The Denisovans interbred with both modern humans and Neanderthals, and traces of their DNA still live on in the genomes of many people today, especially in Asia and Oceania.

The Dragon Man fossil is dated to at least 146,000 years ago, placing Denisovans firmly in Late Pleistocene East Asia alongside other early humans.

This discovery significantly reshapes our understanding of human evolution, suggesting that Denisovans may have been more widespread and advanced than previously thought.

With Dragon Man’s face now unveiled, the once-shadowy Denisovans step into the light as a distinct and fascinating branch of the human family tree.

See more: https://www.ganjingworld.com/video/1fhihnda0lg1UmfR1kQ9Uwmre1mq1c