From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Storm Surge Barrier (New Orleans, USA ) THE FLOODGATES

from Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East employees about how they maintain and operate floodgates to protect New Orleans and surrounding areas from storm surge.

The Flood Protection Authority closed floodgates on Highway 90 in New Orleans East and Highway 46 in St. Bernard Parish at 6 p.m. Friday.

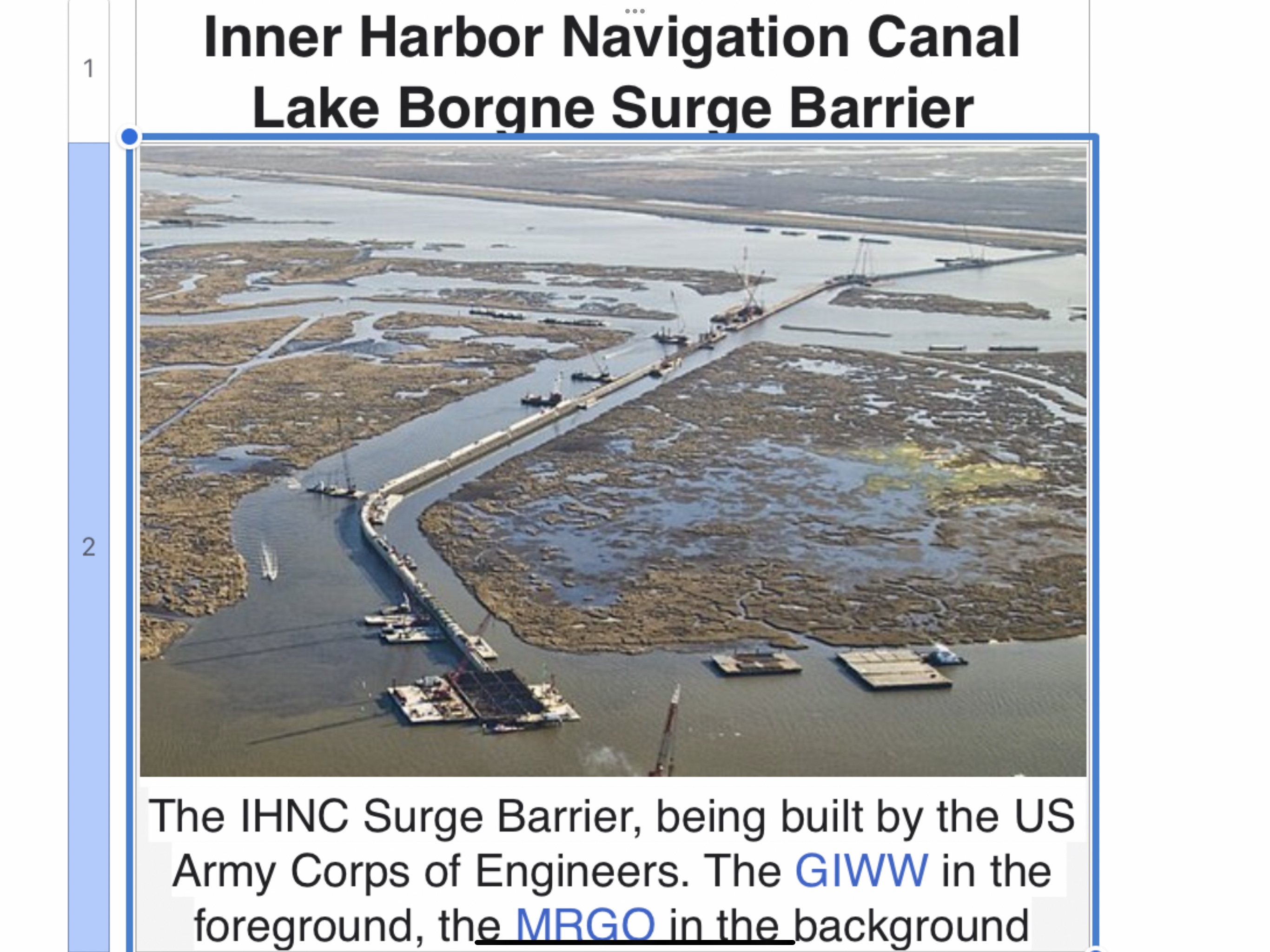

Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Lake Borgne Surge Barrier

The IHNC Surge Barrier, being built by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The GIWW in the foreground, the MRGO in the background

The IHNC Surge Barrier, being built by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The GIWW in the foreground, the MRGO in the background

Crosses

Locale

It’s often called “The Great Wall of Louisiana.” In this video, we show you the nearly 2-mile long surge barrier that is one of the largest flood protection structures in the world. It reduces the risk of flooding from a 100-year storm surge coming from Lake Borgne and the Gulf of Mexico.

Owner

Characteristics

Material

Concrete, steel

Total length

1.8 miles

History

Construction start

2008

Construction end

2013 (major construction)[1]

Construction cost

$1.1 billion[2]

Location

The Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Lake Borgne Surge Barrier is a storm surge barrier constructed near the confluence of and across the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW) and the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) near New Orleans. The barrier runs generally north-south from a point just east of Michoud Canal on the north bank of the GIWW and just south of the existing Bayou Bienvenue flood control structure.

Navigation gates where the barrier crosses the GIWW and Bayou Bienvenue can be worked to reduce the risk of storm surge coming from Lake Borgne and/or the Gulf of Mexico. Another navigation gate (Seabrook Floodgate) has been constructed in the Seabrook vicinity, where the IHNC meets Lake Pontchartrain, to block a storm surge from entering the IHNC from the Lake.

Purpose

The Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC) surge barrier was authorized by Congress in 2006. The barrier is designed to reduce the risk of storm damage to some of the region’s most vulnerable areas – New Orleans East, metro New Orleans, the 9th Ward, and St. Bernard Parish. This project aims to protect these areas from storm surge coming from the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Borgne.

Status

The project was funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. In April 2008, the Corps awarded a construction contract to Shaw Environmental & Infrastructure for the Lake Borgne Surge Barrier, making this project the largest design-build civil works project in Corps history. It is highly unusual for a civil works project to be designed and constructed simultaneously. The expedited process was necessary, however, given the compressed time frame for achieving the 100-year level of risk reduction in 2011.

In October 2008, the New Orleans District Commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers signed the Tier 2 portion of the Individual Environmental Report (IER), which investigated alternative alignments and designs within the location range identified by Tier 1 and explained the impacts of these alignments and footprints, construction materials and methods, and other design details. After the completion of the IER, a Notice to Proceed was issued to Shaw.

In December 2008, the Corps held a groundbreaking ceremony to mark the start of test pile driving. Construction of the barrier’s flood wall began on 9 May 2009. On 21 October 2009 the last of the 1,271 main piles was driven.[3]

On 29 August 2012 (the seventh anniversary of Hurricane Katrina), the barrier was used for the first time, to protect the city from Hurricane Isaac.[4] By June 2013, all major construction had been completed.[1]

Construction

The COE accomplished this project via the design-build delivery method. The main barrier consists of 1,271 concrete piles 66 inches (1.7 m)[5] across and 144 feet (44 m) long, weighing 96 tonnes each. Behind those piles, steel piles are driven at an angle of 2 horizontal to 3 vertical. The steel piles are 288 feet long and are installed in two sections, with the lower 158-foot section driven and the upper 130-foot section fitted on top and welded in place. A precast concrete pile cap is placed on top of the steel batter piles and concrete plumb piles to join them.

Two gates were constructed in the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway navigation channel. One gate is closed with two sector gate leaves, the other gate with a barge swing gate, comparable to a caisson. In the Bayou Bienvenue navigation channel, a vertical lift gate was installed for use with recreational craft and shrimpers.

Features

• Typical flood wall and the MRGO closure flood wall (over a mile long)[6]

• 150-foot wide navigable floodgate on the GIWW—a steel sector gate (42 feet tall)[7][8]

• 150-foot wide navigable bypass floodgate on the GIWW—a concrete barge swing gate

• 56-foot wide navigable floodgate on Bayou Bienvenue—a steel lift gate

• Concrete T-walls on land, at the north and south ends of the Lake Borgne barrier

• Approach walls at the GIWW sector gate and the Bayou Bienvenue gate

• Navigation gate in the Seabrook vicinity

• Marsh enhancement with dredged organic material – As organic material is dredged from waterways in preparation for new construction, it will be deposited in nearby wetlands habitats to enhance environmental conditions

Engineering

COWI Marine North America, formerly Ben C. Gerwick, Inc., provided the detailed designs and drawings[9] for

• The main barrier, including the flood wall and the MRGO closure[6][10][11][12]

• The GIWW sector gate monolith walls and foundation[7][8][13][14][15][16][17]

• The GIWW bypass concrete barge swing gate[9][13][18][19][20]

• The GIWW bypass concrete barge swing gate mechanical operating systems

• Approach walls at the GIWW sector gate

• Scour stone protection for the barrier and gates

INCA (now TETRA TECH, INC.) provided the detailed designs and drawings[21][22][23][24][25][26][27] for:

• GIWW Sector Gate

• GIWW Bypass Approach Walls

• Bayou Bienvenue Lift Gate Monolith

• Bayou Bienvenue Tower and Bridge

• Bayou Bienvenue Lift Gate (with Waldemar Nelson)

• Bayou Bienvenue Approach Walls

Wikimedia Commons has media related to IHNC Surge Barrier.

Sources

1. “IHNC Lake Borgne Surge Barrier” (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. June 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

2. “USA, New Orleans: $1.1 billion surge barrier construction works half way”. Dredging Today. February 2010.

3. “Archithings.com”. Archived from the original on 2010-10-11.

4. “Corps Closes More Floodgates as Hurricane Isaac Approaches – NOLA DEFENDER”. noladefender.com.

5. Construction photo of concrete piles

6. Finite Element SSI Analyses of IHNC Flood Wall

7. A Design-Build Success: The GIWW Sector Gate Monolith

8. Sector Gate Monolith Pile Foundation

9. Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Hurricane Protection Project

10. 2011 ENR Best Civil Works/ Infrastructure Project for the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal

11. “2011 DFI Outstanding Project Award for the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Flood Wall” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

12. “Recent Awards & Achievements”. seaonc.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

13. “Recent Awards & Achievements”. seaonc.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

14. “Past Award Recipients”. seaoc.org.

15. “2013 NCSEA Excellence in Structural Engineering Award Outstanding Project (“Other” Structures) for the GIWW Sector Gate Monolith”. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

16. “NCSEA” (PDF). ncsea.com.

17. “2013 NCSEA Excellence in Structural Engineering Award Outstanding Project (“Other” Structures) for the GIWW Sector Gate Monolith” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

18. “2013 NCSEA Excellence in Structural Engineering Award (New Bridges & Transportation Structures) for the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Barge Gate”. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

20. “2013 NCSEA Excellence in Structural Engineering Award (New Bridges & Transportation Structures) for the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Barge Gate” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

21. USACE, 2016. Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC) Hurricane Protection Project Design Documentation Report. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans District. June, 2016. 798 pp.

22. “Climate Adaptation Knowledge Exchange (CAKE) Case Study”.

23. “2012 ACEC Grand Conceptor Award”.

24. “2014 ASCE Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement OPAL Award”. Archived from the original on 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

25. “2014 ASCE Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement OPAL Award”.

26. “FIDIC’s Outstanding Project of 2014 award”.

27. “FIDIC’s Outstanding Project of 2014 award” (PDF).

External links

1. US Army Corps of Engineers New Orleans District Web Site

2. Nola.com:groundbreaking ceremony today

3. Build It Bigger Season 4: Rebuilding the Levees Archived 2011-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

• Categories: Dams in LouisianaDikes in the United StatesFlood barriersIntracoastal WaterwayBuildings and structures in New OrleansFlood control in the New Orleans metropolitan area

• This page was last edited on 3 January 2024, at 13:11 (UTC).

Related posts

In the quest to pump every drop of water outside city walls, New Orleans city planners inadvertently sank over half the city below sea level. Fifteen years after Hurricane Katrina, the city continues to slowly sink. But it’s also trying to adapt it tenuous relationship with water; officials and residents want to hold it at bay, sure, but they’re also trying to work with nature … as the city once had to.

katrina #flooding #NewOrleans #stoptheflooding #hurricanekatrina #sealevelrise #erosion

A visit to three different locations in New Orleans to learn about how how drainage works in New Orleans, the impact of pumping on the city, and different forms of green infrastructure and water management that are increasingly visible across the city.

Photographs of the inside of drainage pump stations and of the Palmetto Canal are by Christine “CFreedom” Brown and Maggie Hermann. For more images and information on pump stations, check out https://issue2.mxd.media/.

Director: Liz McCormick

Producer: George Ingmire (Sounds, Traveling, LLC)

This video was created for the SRED 6110 course and the Water Leaders Institute in summer 2020. Thanks to the Tulane School of Architecture and Casius Pealer from the Master of Sustainable Real Estate Development program.

Ten years ago, the levees and flood walls meant to protect New Orleans failed against the force of Hurricane Katrina. Since the catastrophe, roughly $14 billion have been spent to upgrade the city’s storm defenses. But is that sufficient? William Brangham reports.

View the full story/transcript: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/n…

New Orleans’s NewHurricane Defences/ Strip the City

New Orleans lies up to 10 feet below sea level and is surrounded by water. When a hurricane hits, the city is threatened from all sides. | For more Strip the City, visit http://science.discovery.com/tv-…

Subscribe to Science Channel! | http://www.youtube.com/subscript…

Watch full episodes! | http://bit.ly/StriptheCityFullEp…