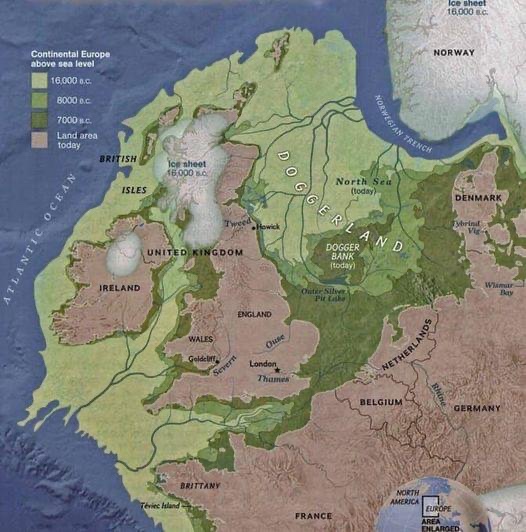

During the Mesolithic period, approximately 10,000 years ago and before the glacial maximum waned, Doggerland existed.

It was made of marshes, swamps, wooded valleys and hills, and most likely inhabited by humans, migrating wildlife: a seasonal hunting ground for people living there.

When the ice melted, sea levels began to rise, inundating vast areas of low-lying land. Doggerland, an expansive region that stretched from present-day Scotland to the Netherlands, succumbed to the encroaching waters.

Dogger Bank was the last section of land to resist as an island before submerging underwater. The area today is known among fishermen as a treasure trove of archaeological finds, offering glimpses into the lives of ancient inhabitants.

While rising sea levels played a significant role in Doggerland’s submersion, a catastrophic event known as the Storegga Slide further altered its fate. A massive undersea landslide off the coast of Norway triggered a tsunami that inundated the low-lying plains, accelerating the demise of Doggerland.

Doggerland served as a crucial land bridge for early human populations, facilitating the movement of people and wildlife between Britain and the continent. This connectivity influenced the dispersal of cultures and the exchange of resources, shaping the prehistoric tapestry of Europe.

Over the years North Sea fishermen have found hand-made bone artifacts, textile fragments, paddles, dug-out canoes, fish traps, a 13,000-year-old human remain, a woolly mammoth skull and a skull fragment of a 40,000-year-old Neanderthal.